Massimo Bottura: Culinary Revolutionary

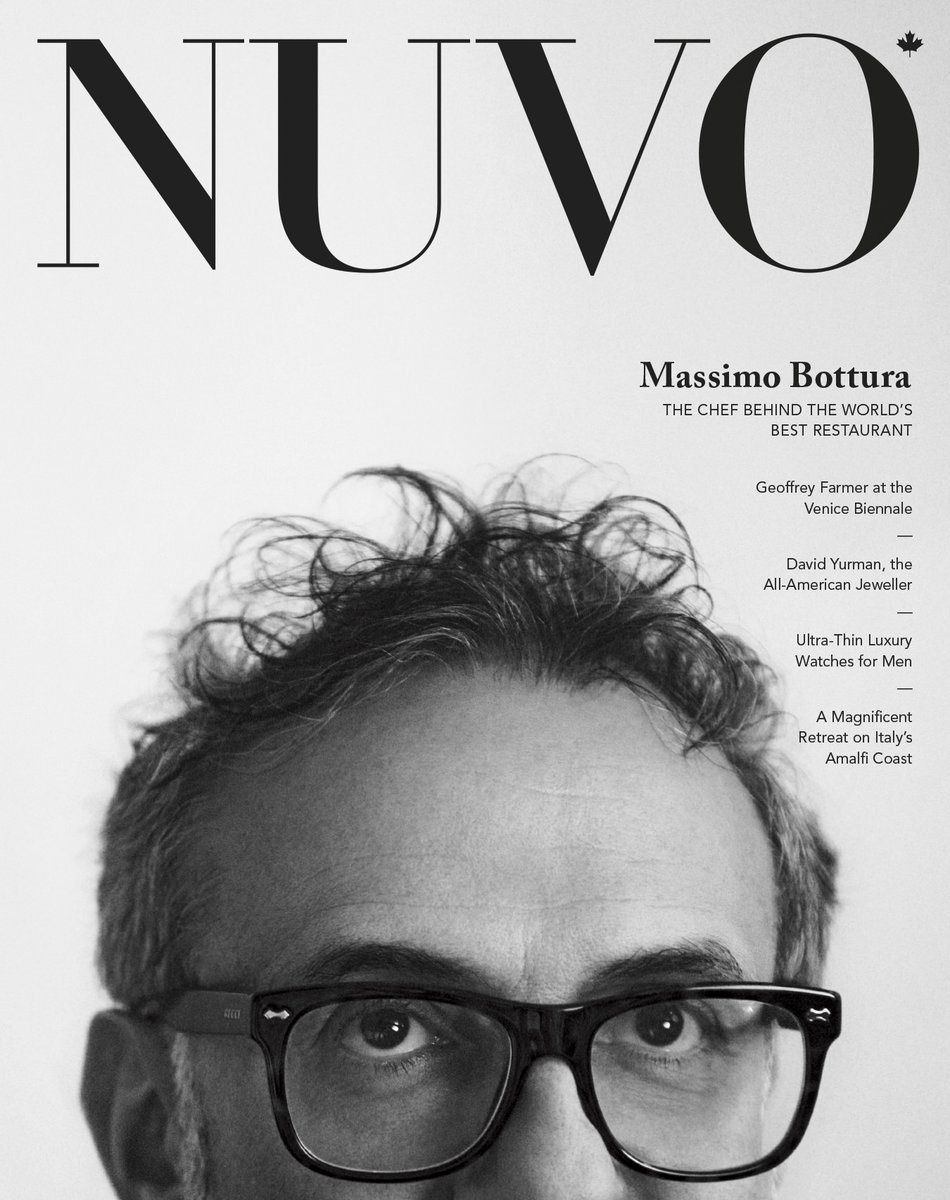

The first time I saw Massimo Bottura, he was standing outside the kitchen of Hotel Bellariva, on the shores of Lake Garda in northern Italy. It was a crisp afternoon in May of last year, the water and air so still the scene could have been a painting. The hotel, a former villa built in 1904, bore classical proportions from an even earlier era: it could have been the Risorgimento but for Bottura, who, with his thick black frames, salt-and-pepper hair and complementing beard, and New Balance sneakers shifting in the pebbles of the driveway, cut a thoroughly modern figure. He was there to prepare a special meal for a group of automotive journalists brought there to celebrate the release of the new Maserati Levante. A Modenese by birth, Bottura told us over dinner, “I am passionate about two things: fast cars and slow food.”

Most chefs do these corporate gigs for the money and put in minimal effort. But not Bottura. He had brought a large portion of his kitchen staff to the hotel, nearly two hours from his restaurant in Modena, Osteria Francescana, and they turned out classics from its menu like “Autumn in New York,” an assemblage of vegetables inspired by both the Union Square Greenmarket and Billie Holiday’s melancholic tune, and “Beautiful, psychedelic, spin-painted veal, not flame grilled,” in which the meat is rolled in vegetable charcoal, then cooked sous-vide and plated atop an alarmingly bright array of splattered vegetable pureés and reductions. The dish itself draws inspiration from Damien Hirst’s 2003 work, Beautiful Naked Psychedelic Gherkin Exploding Tomato Sauce All Over Your Face, Flame Grilled Painting. One needn’t understand the allusion to appreciate the flavours. I was impressed not only by Bottura’s fantastical creations, but that he showed up. He really showed up.

Half a year later, Bottura is bent over his iPhone in the library lounge of the NoMad Hotel in New York. He’s a modern man in a modern world, wearing all black and thumbs a-blur like everyone else in the room. Much has changed—everything, and nearly nothing—because, after lurking in the top 10 for the last five years, Osteria Francescana had finally been named the best restaurant in the world in June 2016, according to the S.Pellegrino World’s 50 Best Restaurants list. The ranking, though not without flaws, is enormously influential and overwhelmingly authoritative.

"Modenese by birth, Bottura told us over dinner, “I am passionate about two things: fast cars and slow food.”

Bottura has joined the elite ranks of creative nomads, who spread their visions worldwide with the help of frequent flier miles (his life is a constant blur of conferences and airport lounges). His efforts to make a social impact through his cooking took Bottura to the Rio Olympics, where he organized a soup kitchen in Lapa, a favela, or slum, in Rio de Janeiro, called Refettorio Gastromotiva. Another of the chef’s soup kitchens—Refettorio Ambrosiano, which fed refugees and the homeless for Expo Milano 2015—was chronicled in the documentary Theater of Life by Montreal-based director Peter Svatek.

A few hours before our latest reunion, Bottura had been wandering by the High Line, an elevated park on Manhattan’s west side, when he came across a tree growing next to a basalt column. It was an extension of a 1982 installation by artist Joseph Beuys called 7000 Eichen that began in Kassel, Germany at Documenta 7, and spread to New York in 1988. Bottura took a short video, looking up through the branches as the snowflakes fell. Now he was working on a caption for Instagram: “Creativity is also about poetry!” he wrote. “Make visible the invisible. NY State of mind J. Beuys. We should never stop planting.” He posted the video and, immediately, his phone nearly twitched off the table with likes as the post ricocheted across the worlds of cuisine, art, innovation, and pop culture in which Bottura holds immense sway.

For a radical who overthrew thousands of years of culinary history, Bottura is warm and friendly. He speaks English with near fluency and incredibly quickly. He is Italian and gestures dramatically, his fingers constantly coming together and apart, touching his temple and cutting the air. His mind works with such rapidity and traverses such vast terrain that one often feels he’s misheard a question until about five minutes into the reply, when it becomes clear he just took the scenic route.

Though it is true that Massimo Bottura is a chef—the best chef in the world, no less—he comes across as an artist whose medium happens to be food. He’s heard that before. “Many artists have told me I’m more artist than an artist,” he says, “but I always answer, ‘I am an artisan, inspired by artists.’ ” Bottura makes that distinction because in order for his art to be consumed, it has to taste good and in order for it to taste good, Bottura has to have an artisan’s mastery of craft. In his case, the craft is even more important because so often the ideas that he seeks to express through his food are so complex, his technique must be similarly sophisticated to adequately convey them.

Take one of the signature dishes at Osteria Francescana, “Bollito, not boiled.” This title, like many on his menu, contains a jeu de mots that underscores how seriously Bottura takes humour. (Bollito means boiled in Italian, so the dish, fully translated, would be “Boiled, not boiled.”) Other items on the menu of the 12-table restaurant include “An eel swimming up the Po River,” “Cod Mare Nostrum,” and his most famous dessert, “Oops! I dropped the lemon tart,” a painstaking re-creation of a dropped lemon tart. “It’s perfect imperfection,” explains Bottura.

Though it is true that Massimo Bottura is a chef—the best chef in the world, no less—he comes across as an artist whose medium happens to be food.

For “Bollito, not boiled,” he was inspired by bollito misto, a traditional preparation of boiled meats—belly, cheek, tail, tongue, etc.—that dates back to the Middle Ages. Today, to the extent that it is served, bollito misto arrives as the second course of a fine-dining meal in a silver guéridon, in which each meat resides in its own individual compartment as if in a carnivorous apartment building, and is accompanied by a panoply of brightly coloured sauces like mostarda, salsa verde, and peperonata.

When Bottura opened Osteria back in 1995, taking over the lease of a comfortable traditional restaurant, the previous occupant had left an elaborate trolley that had been used for this purpose. Not one to let an opportunity go unexplored, Bottura bent his mind to this old-fashioned recipe. As he relates in his 2014 monograph Never Trust a Skinny Italian Chef, he asked a local butcher to deliver bollito misto cuts to the kitchen made from Fassona cattle, a heritage breed from Piedmont. When the cuts arrived—so rich, so pure, so fresh—Bottura revolted from boiling them to grey homogeneity. “Are we sure our culinary traditions respect our ingredients?” he asked his staff. When the answer, a resounding silence signifying no, came back, Bottura writes, “In an instant, we had freed ourselves from our obligation to tradition … Everything changed.”

Instead of boiling the meat, he separated each cut into its own vacuum-sealed bag and cooked them sous-vide individually, at temperatures and times ideal for each. The meats came out rich in colour and delicate in texture, with their true flavour and identity preserved. The result gave a nod to the past, but looked toward the future. But, as Bottura notes, the dish was only partly there. That summer, on a trip to New York, the other half came together. Bottura noticed the Manhattan skyline over the trees of Central Park and his mind returned to the bollito. When he got back to Italy, he cut the blocks of meat into small building-like blocks and transformed the traditional accompanying sauces into fluffy parsley air, red pepper gelatine, and a drop of Campanine apple mostarda, all three mimicking Central Park’s foliage.

The plate as it is served today, as strange as it sounds, is a meaty skyline in miniature that spans epochs and worlds. Centuries of Italian tradition, the audacity of innovation, an obsession with technique, and the possibility of modernity commingle, and the man who summoned them together is Massimo Bottura. “The most important thing, as in art, is the idea,” Bottura says. “I can buy technique from the best Japanese guys or the best sous-chef, who worked for [Alain] Ducasse for 35 years. I hire him and I have the best sauce, but the idea—that can only come from me.”

Though he describes himself as an artisan, I don’t buy it and I don’t think he really does either. Bottura operates with a clarity of vision more often associated with the greatest artists of our time than with the greatest craftspeople. His obsession isn’t with technique for technique’s sake, but as a means to communicate his philosophy. And that philosophy is twofold. Bottura’s first claim is that we must move forward, and that the way forward is experiencing our world with an open mind. Just as importantly, according to him, confronting traditions is the only way we’ll preserve them for the future.

“I’m sitting on centuries and centuries of tradition, but I filter everything through a contemporary mind.”

In a political landscape darkened by clouds of revanchist nationalism, it’s a message that’s even more relevant today. “Especially now,” says Bottura. “Slavery to nostalgia is the most dangerous, because it generates the old past.” To buttress his case, he draws a conceptual line between Ise Jingu, a shrine in Mie Prefecture in Japan that has been torn down and rebuilt every 20 years for the last 1,300 years, and the tale about the first time a Neapolitan baker turned traditional focaccia into what we now know as the Margherita pizza in 1889 to honour the queen consort of Italy, Margherita of Savoy. “In that moment,” Bottura says, “there was an urgent moment to create,” he says. “It was an innovation, and that innovation became tradition because it was extremely well done.” Similarly, Bottura sees himself riding on the waves of his forebears, yet is intent on staying on the crest. “I’m sitting on centuries and centuries of tradition, but I filter everything through a contemporary mind.”

The corollary or perhaps the foundation of Bottura’s obsession with the contemporary mind is the importance of culture. Bottura is a cultural polyglot. One of the things that impresses me most about him is that he doesn’t make a distinction between Bob Dylan’s Nashville Skyline, one of his favourite albums; the work of Italian artists like Maurizio Cattelan and Francesco Vezzoli, among the many that hang in the restaurant; the refined technique of Alain Ducasse, under whom he apprenticed at the Hôtel de Paris; or the whine of an eight-cylinder Ferrari engine roaring through Modena’s narrow streets. It takes enormous talent to bring these disparate disciplines into conversation, but if you can, as he can, the conversations are thrilling.

Now, as violence and political crises threaten the armyless and borderless regions of culture, Bottura sees his mission of being a cultural evangelist as his primary vocation. To that end, he’s helped turn the spotlight that accompanies heading the best restaurant in the world on issues like food waste; his non-profit organization, Food for Soul, also draws attention to that cause. From the refined preparations at Osteria, in which Bottura routinely champions what he calls “working-class heroes” such as sardines, pasta e fagioli, and a fish called rudd, to the thousands of dinners made from what would otherwise be discarded food served at the Refettorio Gastromotiva for some of Brazil’s poorest citizens, to gazing through the branches of an oak tree in New York, Bottura makes the case that that which we toss should not be thrown away; that which we overlook should be noticed. “I am constantly working to make the invisible visible,” he says. “Culture creates culture,” he continues. “Violence creates violence. If I stand even in this moment on the side of culture, perhaps I can make a difference and show that we all must be brave and keep fighting.”