Gay Talese, holding a gin martini in one hand, sat in a dark corner of the bistro, before an attractive blonde who stood waiting for him to say something. “I’m having the sea bass as my main course,” he said, “but I’m going to have a beer right now.”

“Beer?” she asked doubtfully, since he had a half-full martini in hand.

“Beer,” he repeated. “A light beer. What do you have in a bottle?”

“It’s all draft,” she replied.

“If it’s gonna sit there for a half-hour, I don’t want a beer. I’ll have the beer when I have the main course. Sit it here,” he said, jabbing a finger in the space beside his plate.

“Do you think I’m going to forget?” asked the waitress. “I’m taking this personally.”

“Darling,” he replied, “you’re going to forget.”

At five o’clock every night, after a full day’s writing, Gay Talese watches the news on television. Two hours later he embarks on the Talese Dinner Circuit, visiting one of six restaurants near the Upper East Side townhouse he shares with his wife of sixty years, Nan Talese, to drink a gin martini followed by a cold light beer served simultaneously with the arrival of his dinner. On a Tuesday night a few weeks before the publication of High Notes, the latest collection of the author’s essays, Talese carefully traversed 61st Street and descended the short flight of stairs to the dining room of Maison Hugo.

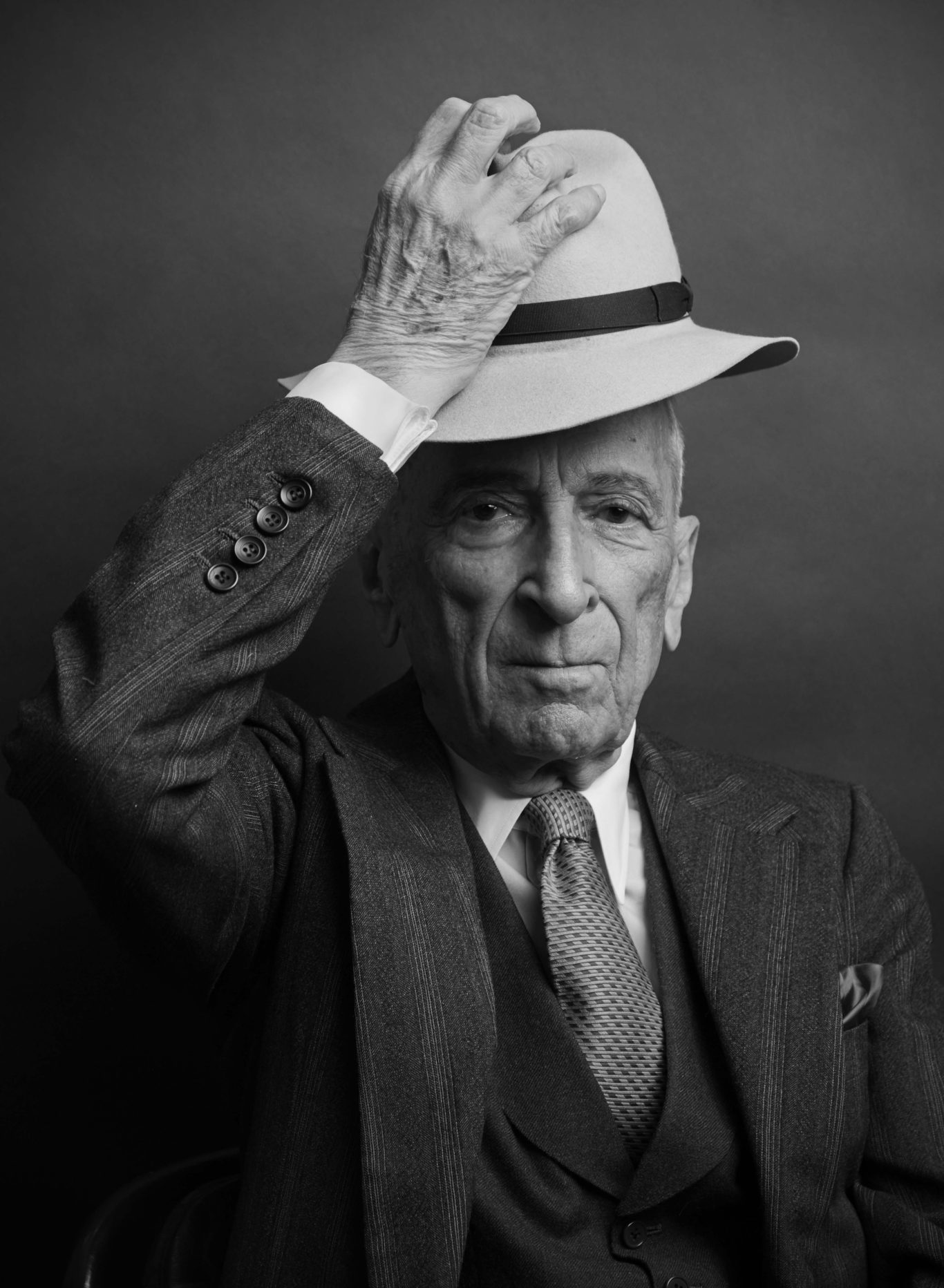

Still slim, and as nattily dressed as ever in a three-piece suit, Talese folds into his chair like a switchblade. At 84, he remains one of the world’s great listeners. When he’s engaged, he claps a hand over his lips, then lets it slide down to a chin-stroke. A literal gobsmack. It is immensely satisfying to be listened to by him — which is, perhaps, why so many people, from DiMaggio to Ali, from opera singers to cabbies, have splayed themselves before him. (The exception, of course, being Ol’ Blue Eyes.)

The articles that form the body of High Notes, taken mostly from the New Yorker and Esquire, offer proof that Talese is both an inner- and outer-watcher. Whether the subject is a stuffy-nosed center of an entertainment-industrial complex or a younger version of himself, Talese peers so hard at the external circumstances of a subject, the interiority is thereby revealed. This is the foundation of the New Journalism he pioneered in the 1960s. “Nonfiction is still not treated with the respect and delicacy of fiction,” Talese laments. “Nonfiction is concerned with the public life; fiction with the private. I’ve always wanted to go into private life.”

As for his own life, it has offered much to examine. (Even — especially — recently. Headlines of his foibles led the news twice last year, first during a Boston University panel discussion when he was unable to name any female writer of his generation he admired, and then with the publication of his pervy porny prosy The Voyeur’s Motel.) It is the inclination of kings to survey their kingdom, especially if, as is the case with Talese, one’s reign has been so long, eventful, and prosperous. And tonight, his recall settles around one resonant moment from more than half a century ago.

“Nine days on a fucking boat,” he says. It’s 1953. Talese is serving as a tank officer, stationed in Frankfurt under Creighton W. Abrams, the man for whom the Abrams tank is named. On furlough, he decides to visit his extended family in Maida, the small town in Calabria that his father left at age seventeen on a boat to America. In his smart lieutenant’s uniform, Talese stands out on the train from Naples, a three-hour trek across the ruined countryside. Yet it is not a feeling of pride that fills the Talese who recounts this now, as he waits for his beer, patience fraying. It’s guilt, and guilt’s public face, shame.

When he finally found his people, he saw how miserably poor they were and how, though their faces bore the equine features of his own, their lives were lived centuries away. There was dirt beneath their nails, dirt on their faces, dirt on the floor. Talese’s father was a tailor — the “James Salter of tailors,” he says — who insisted that his son dress impeccably, down to the mathematically rakish angle of his fedora. These relatives, who shared with him their last name, were the Gay Taleses that could have been but for the nine-day journey on a boat that his father took in 1921. “It was an accident of voyage, an accident of water and a ship. Nine days that changed history.”

But what still makes Talese cringe today is the regard with which this Calabrian branch held his younger self. “They thought they had General Dwight D. Eisenhower before them,” he says, miserably. “And here I am, a tailor’s son with my goddamn clothes. I couldn’t wait to get the hell out.” His relatives’ overestimation embarrassed him; the circumstances of his fortunate birth an ocean away were in no way his accomplishment to claim. “Nine days on a fucking boat,” he says, “and who takes the boat ride? Selfish, self-serving people. Miserable, shitty people take the boat ride. Nice people stay home.”

Even today, despite the townhouse and the Cristiani suits, the closetful of custom shoes and the unrelenting tide of accolades, Talese still sits like a sparrow on a too-narrow perch, restless and vigilant, always on edge. He forgets neither slights nor acts of kindness. He can recall every critic’s cutting word. “I could tell you who they are, what’s happened to them, where they live, what their zip code is. I know their Social Security number.” Donald Trump, who used to give him rides in his limo back from Steinbrenner’s box at Yankee Stadium, will always be a good guy for, in 1986, when Talese was the vice president of PEN and “crazy, fat” Norman Mailer the president, having put up two hundred writers for free in the ballroom of the St. Moritz Hotel. “I got twenty-five free rooms in a ballroom for two weeks. Zero. That’s what counts.” He remembers who sends thank-you notes. “Bloomberg, yay. Trump, yay. Obama, pssh.”

Talese clings to his views as only someone who fears they’ll be taken away does. Views and truths and all other things too. “I have a tough time saying goodbye,” he admits. “I have the same wife, the same house, the same typewriter, the same car. Everything I have that I bought I don’t get rid of.” And he doesn’t forget what he wants.

The sea bass is served, but the beer has not yet arrived. Talese is not pleased. “Where is the woman who took my beer order?” he demands, his voice rising with ire. “She’s in Staten Island somewhere.” He looks around. “Hey you!” he says, flagging another waitress down, “you were going to bring me my beer.” He’s got the wrong one — it was the blonde, he’s reminded. “I don’t care,” says Talese. “Outsourcing is killing our country.”

After a couple of minutes, the beer arrives. For a moment, Talese gazes at his own reflection in the glass, golden and distorted. Then he brings it to his lips and takes a long, studied sip.