Wayward Writer

To be surprised, of course, one has to have expected something in the first place. That there are so many expectations as to how and where the author of American Psycho and a slew of other equally misanthropic works might live is testament to the power of his work and the heft of his public persona. Ellis is 49, and there’s still a glimpse of the boyish face seen in so many photographs at the table of some hot Manhattan restaurant years ago, but it’s caught now only fleetingly. Perhaps the only subversive thing about him today is that he’s wearing a winter jacket, inside and in Los Angeles.

This is what has been called by Ellis and others the “post-Empire” Ellis, a portrait of the author as a middle-aged man. Ellis belonged to the Literary Brat Pack, which included authors Jay McInerney, Tama Janowitz, and Mark Lindquist. The extent to which this group dominated New York’s literary and pop-culture scenes in the late 1980s and early 1990s would be hard to imagine if Ellis had not exhaustively chronicled the gallons of Cristal drank, cocaine consumed, cartons of cigarettes smoked, hearts broken, critics awed, parties thrown, and drug-dependent book tours undertaken. But in 2003, Ellis moved from New York, where he first made it, and then back to Los Angeles, where he was born, to break into the movie business. “The party was over,” he explains. But the extent of his success, or lack of it, accounts for the Florida-meets-WeHo apartment complex and, perhaps, the absence of visible cocaine.

Ellis essentially lives within a five-mile radius of his home, and he spends most of his time behind a computer. “I have a very small orbit,” he admits. “I never cross Vine.” Recently, his friend Nick Cave was playing a show at the Fonda Theatre, two blocks outside of his limit. “I told Nick, ‘I don’t think I want to come to your show.’ And he said, ‘What? That’s crazy.’ I said, ‘Sorry, it’s not within the border.’ ” It’s a surprisingly proscribed life for such a boundary-trouncing figure.

These days, in Hollywood, Ellis is still drawn to the predatory, vulnerable, and seedy side of humanity. His métier is not the better angels of our nature but the worse. Among his unrealized ideas are a film based on the suicide of a pair of young artists called The Golden Suicides; a revenge thriller titled Bait; a couple of television shows; and one film, The Informers, that did get made, but so poorly that Ellis hardly mentions it. His latest effort to break into the talkies is The Canyons, a film he wrote, which stars Lindsay Lohan and adult film star James Deen. The movie, currently slated for North American release this August, is directed by Paul Schrader, the man who made Taxi Driver and Raging Bull. The film itself is a feat of scrappy democracy, or, if you prefer, demagoguery: funding was crowdsourced via Kickstarter without any studio backing. Schrader, producer Braxton Pope, and Ellis auctioned everything from a link to download the movie poster (available to those who made a $1 donation), to a money clip autographed by Robert De Niro (for $10,000). In two months, the group raised $150,000. That, plus $30,000 put up by each of the principals, along with a bunch of deferments, was enough to make the movie.

Bret Easton Ellis essentially lives within a five-mile radius of his home. “I have a very small orbit,” he admits. “I never cross Vine.” It’s a surprisingly proscribed life for such a boundary-trouncing figure.

Like most of the projects in which Ellis is involved, this one is diaphanous, shimmering between fiction and reality. It’s also controversial. The plot involves a failing actress named Tara, “the type of girl who came out to Los Angeles, but for whom things didn’t quite work,” explains Ellis. “The auditions dried up, and she finds a wealthy man to take care of her.”

Tara is played by Lohan, herself a girl who came out to Los Angeles and for whom things didn’t quite work out, for whom the auditions dried up, and who—although she hasn’t found a wealthy man to take care of her—has at least found a movie to call home. (One of the reasons Lohan agreed to star in The Canyons was that she had become uninsurable as a star in major Hollywood pictures due to her unpredictable behaviour.)

As described on the Kickstarter website, the film is a “contemporary thriller [that] documents five twenty-something’s quest for power, love, sex, and success in 2012 Hollywood”—but it really centres on Tara; her boyfriend, Christian (played by Deen); and her ex-lover, Ryan (played by Nolan Gerard Funk). As you might expect from Ellis’s pen and a movie in which the hero is a porn star, there’s plenty of sex and violence; Lohan was contractually obligated to participate in a scene depicting a graphic foursome.

Both South by Southwest and the Sundance Film Festival rejected the film. But in February, IFC Films announced it had picked it for North American theatrical distribution, and early reviews have lauded Lohan’s performance as brave, fearless, and, according to one website, the only way she can save her career. “The movie isn’t the greatest thing in the world,” says Ellis. “But it’s good.”

It’s a tempting trap, and one into which many journalists writing about The Canyons have fallen: to cast the film—a story about things not working out for people in Hollywood—as a meta-story of things not working out for people in Hollywood making a film about things not working out for people in Hollywood. The allure is apparent: Paul Schrader hasn’t done much at all since Taxi Driver and Raging Bull. Lindsay Lohan is Lindsay Lohan. James Deen is trying to make it in the world of non-adult film. And there’s something deeply appealing—albeit in a schadenfreudian way—about seeing Bret Easton Ellis, a bad boy for whom so many good things kept happening, finally have to sweat it out on the line for once.

Thus far, the purest expression of this type of New Criticism fallacy has come from Stephen Rodrick, who wrote a widely discussed article for The New York Times called “Here Is What Happens When You Cast Lindsay Lohan in Your Movie”. His main point was that The Canyons is the last stop for a bunch of washed-up has-beens and (in Deen’s case) never-weres.

Unsurprisingly, Ellis disputes this account, at least as it pertains to him. “This has been the best year for me professionally,” he says. In addition to the film, he’s writing another novel, as well as an eight-hour television series called The Follower about a cohort of dissolute, privileged twentysomethings living in New York. But, he says, “unbeknownst to everyone else, one is a crazy murderer. It’s like Girls meets Dexter meets The Social Network.” He and Pope are also working on a horror movie set in a college town. “It’s about 20-year-olds,” says Ellis. “I guess I’m regressing. As I get older, my characters get younger. Pretty soon, I’ll be writing about children.”

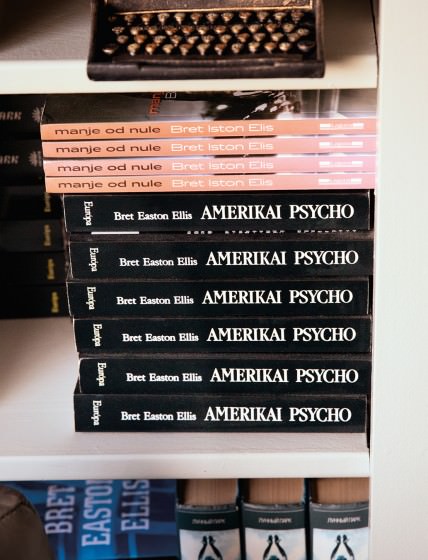

At this point, Ellis and I are sitting in his very warm, very plain home office. He had led me to his apartment, through a tiny kitchen, past his 26-year-old boyfriend, Todd Michael Schultz, a tea blogger and musician. Among the books on the smallish bookshelf are a dozen copies of Imperial Bedrooms; a few Hungarian editions of his 1987 novel, The Rules of Attraction; an anthology of film criticism by Pauline Kael; and Play It as It Lays, by Joan Didion, perhaps the only writer about whom Ellis has ever said anything nice. (“I would rewrite paragraphs of hers just to see how she would do it,” he once said.)

Here’s another surprise: he’s actually just a guy trying to make it. This is surprising for Bret Easton Ellis, who is fond of creating monstrous characters and naming them Bret Easton Ellis. As a student in Less Than Zero, his creation—Clay, get it?—cavorted and caromed around the city, consuming tanks of gas and gobs of drugs. In Lunar Park, he appears as Bret Easton Ellis, a horrible father, a worse husband, and, in general, just a real prick. In Imperial Bedrooms, Clay appears again, and he’s not much better, though he is older.

In fact, there’s nowhere in the man’s oeuvre that he is not crummy. There are no worlds among those he creates that aren’t tyrannies of bad behaviour, wastelands of capitalism, stylish cesspools of venality. Darkness sucks the oxygen from these worlds, and the best that can be said about them is that if one listens closely, the faint scratching of a tender-hearted soul can be heard like a puppy dog locked in a basement of a brothel. “I really knock myself down as a sort of base character,” Ellis admits. “I really degrade myself a lot. It’s part narcissism and part defence mechanism.”

But despite it all, there is a naïveté and, perhaps, goodness in Ellis’s protagonists—and in himself. If the world is so dark, he seems to argue, a pure soul can’t be blamed for being dark, too. Even the radically outré project of The Canyons, coming after a long string of studio disappointments, could be seen as a touching act of naive faith at another go. “I’ve been called a big baby by people who know and love me,” says Ellis. But saying that he’s just a sweet guy trying to make it by writing satirical odes to depravity is not quite true.

From his office, from within these brown walls and on top of this beige carpet, Bret Easton Ellis trolls the Internet ruthlessly. He has more than 400,000 Twitter followers and often takes to the feed to be outrageous and sensationalist (to such an extent that, as he admitted recently, “I’ve found out that many followers of the Official and Verified @BretEastonEllis enjoy it mainly because they think it is a parody account”). For example, here’s what he tweeted about Kathryn Bigelow, who won the Academy Award for Best Director for her 2008 film The Hurt Locker: “Kathryn Bigelow would be considered a mildly interesting filmmaker if she was a man but since she’s a very hot woman she’s overrated.” (He later publicly apologized to Bigelow). He’s also used Twitter as an outlet to defend Paris Hilton’s homophobia, talk smack about the deceased author David Foster Wallace, call for a ban on popcorn at the movies, and blame bullying victims for being bullied. Like most of the projects in which Ellis is involved, his Twitter is shimmering between fiction and reality. But unlike in a novel or a film, Ellis has only his handle to shield him. Handles, of course, are meant to be grabbed. They don’t shield anything at all.

Ellis blames the furor each of his Twitter-based trespasses has incited on what he calls “the oversensitive nature that has blossomed around everything”—but he admits that Twitter may have become more trouble than it’s worth. He sounds very weary as he says this, and the late afternoon light slanting through the shades turns them into bars that fall across his face. This is Bret Easton Ellis in the prison of Bret Easton Ellis–ness. And all of Los Angeles, from the freeways with their twice-daily standstills to the canyons with their bleached-out stories of human frailty, seem at once achingly near and just out of reach.