Up at the old atelier.

On the ground floor of the undisclosed location of legendary couturier Dapper Dan’s atelier somewhere in Harlem, framed photographs of famous clients including Salt-N-Pepa, Floyd Mayweather, and the Fat Boys decorate the walls. A coffee table groans with a stack of books including A Time Before Crack, Who Shot Ya? Three Decades of Hiphop Photography, and Harvey Stein’sHarlem Street Portraits. Bolts of iridescent Gucci fabric shimmer on a shelf. And heady conversation competes with the booming 808-and-synth beat of a newly released song by Jay-Z and Beyoncé, “Apeshit”.

Here in the front room, friends and family of the man born Daniel Day hold court. His adult daughter, Danique Day-Loving, is queen. A principal at the nearby Success Academy Harlem 1, Day-Loving has been a frequent visitor at the atelier since it opened to select Gucci clients and friends of Dap, as he is called, in January. Next to her is someone Dap met earlier that day, a doctoral student of education leadership at Harvard who had never been to Harlem before. Sitting on a settee is a London-based financier childhood friend of Dap’s son, Jelani Day. Jelani, who acts as his father’s brand manager, stands nearby, phone stuck to his ear. While Dap is finishing with a client upstairs, the conversation downstairs runs the gamut from the intricacies of negotiating educational institutions in New York City to the importance of being aware of inherent bias in the classroom. Everyone from the apostle Paul to sociologist Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot gets name checked in quick succession. It’s hard to imagine such a discussion happening in Dap’s old atelier. But then again, no one could have predicted his rise and fall and rise again.

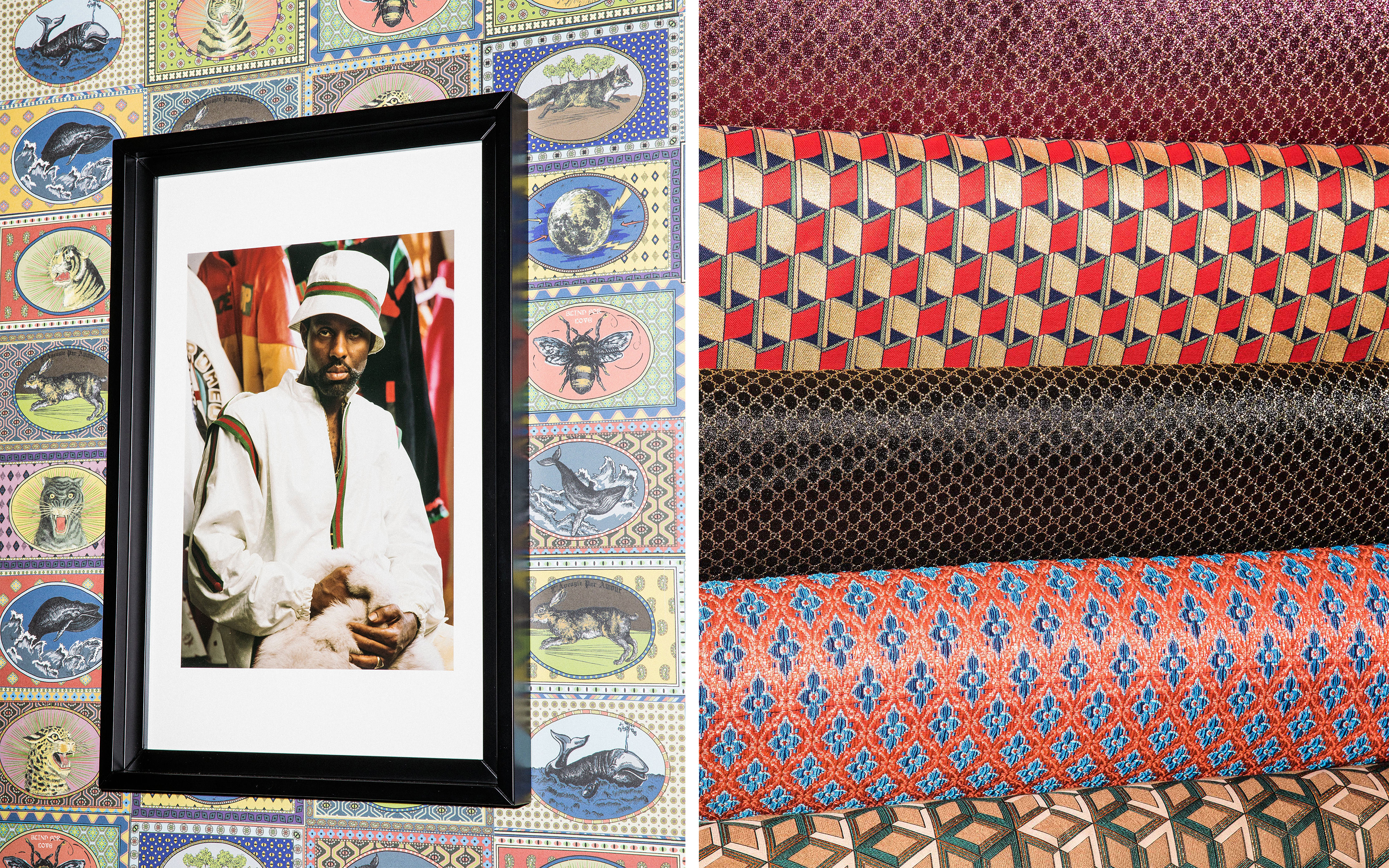

Left: Dapper Dan wearing his own Gucci-inspired rain coat and hat. Right: Bolts of Gucci fabric.

Dap is in constant motion. He walks with a slight limp. He seems to know everyone in the neighbourhood and though the exact location of the atelier on Lenox Avenue is largely kept secret, Dap spends a fair amount of time out front on the stoop. In the space of a few minutes, he’s greeted by a half-dozen locals, including politicians, high school students, and guys from the block. He welcomes them all into the atelier, client or not. This open door policy hasn’t changed since the early days. It’s almost impossible to imagine the conversations that occurred back at Dapper Dan’s original Harlem atelier, located at 43 East 125th Street, a few blocks northeast of where he is today. In the 1980s and ’90s, the 24/7 shop was a magnet for Harlem’s rough-and-tumble hip-hop musicians, sartorially minded crack kingpins like Alpo Martinez and Azie Faison, late night hustlers, and world-class athletes. It was, famously, the site of a 4 a.m. showdown between Mike Tyson and Mitch Green. The building has since been demolished, and in its place a Harlem Children’s Zone has risen. But it’s just as well—if those walls could talk, every word would be bleeped out.

What drew people to Dapper Dan’s shop were his unlicensed and exuberant versions of pieces by well-known luxury labels such as Fendi, Gucci, Louis Vuitton, and MCM. His garments were wrought in fabrics and furs, and using those eminent logos (dyed into leather with toxic ink on the third floor of the shop and sewn into garments by a team of 27 Senegalese tailors, who worked around the clock) Dap created over-the-top designs that came to embody early hip-hop culture. They were audacious, braggadocious, undeniably fly. The garments were a profusion of patterns on patterns, a proclamation of self-worth, inspired by Dap’s own travels through Africa—Ghana, Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda, Nigeria, Ethiopia, Egypt, and more—as a teenager with the New York Urban League. “I went to Africa lookin’ for me, to see what it was like being a black man over there,” he tells me, after I finally meet him in the second floor VIP fitting room. “That’s where I came into consciousness.” Inspired by the anti-colonialist message of Kenya’s fiery president Jomo Kenyatta, Dap realized, “We are responsible for what happens to us. That doesn’t excuse whoever puts their foot in our neck, but what it does explain is how we allow someone to put their foot in our neck.”

That lesson stuck with him through his years as a professional gambler, so when he saw that Harlem’s hunger for luxury wasn’t being met, rather than throw up his hands, he decided to yank back the symbols of prestige and make them his own. “I Africanized the garments,” he says. “I blackified them.”

Dap tapped into a vast and growing market. Soon he was churning out everything from car interiors to sweatpants to custom fur-lined leather jackets. There was no mistaking a Dapper Dan creation—the chimera of high fashion brands and Dappian swagger was immediately recognizable. Something new had been born. “Fashion is the most tangible for the aesthetics,” he explains. “But for fashion to be whatever, it has to have a platform. In the ’80s, we got hip-hop and we got the crack epidemic. There’s all this money, this liquid money moving around. That’s where this new culture formed.”

From 1982 to 1992, Dap was Savile Row for black culture. Almost every single hip-hop star sported a Dap-designed outfit.

According to marketing mogul Steve Stoute’s book, The Tanning of America: How Hip-Hop Created a Culture That Rewrote the Rules of the New Economy, “Dapper Dan played an extremely important role in introducing the founding hip-hop generation to couture brands. What’s more, he translated those elements of haute couture into applications that were understandable to young, hip, aspirational taste makers … Because of Dan, I believe, an appreciation of specific couture brands became inbred in hip-hop culture.” From 1982 to 1992, Dap was Savile Row for black culture. Almost every single hip-hop star—and wannabe hip-hop star—sported a Dap-designed outfit. The cover of Eric B. & Rakim’s breakout album (arguably the best hip-hop album of all time, Paid in Full) features the pair in custom black-and-white leather jackets from Dapper Dan, with Gucci’s interlocking Gs front and centre. His rise did not escape the notice of the fashion brands to whom he paid homage. He was constantly harassed by lawyers, mostly retained by Fendi, and his shop was repeatedly raided and his merchandise confiscated. Every time he’d start again from scratch, but by 1992 he had had enough and closed his shop for good.

During Dap’s long exile, the seeds that hip-hop had planted in the Bronx and Harlem in the ’80s and ’90s blossomed. Even as he toiled in the margins, outfitting entertainers and repurposing popular logos and making custom garments, the revolution transformed global culture—high, low, and in-between. It all came to a head for Dap in 2017. That was when Gucci’s creative director, Alessandro Michele, debuted a fur bomber jacket with puffed sleeves that struck many as derivative of an earlier Dapper Dan creation. The circle of appropriation and reappropriation seemed complete. A Twitter uproar ensued. “Did Gucci Copy ‘Dapper Dan’? Or Was It ‘Homage’?” asked The New York Times. It was a stunningly simple reversal of power. Had The Times even bothered to cover Dapper Dan in the ’80s, the question would have been the exact opposite. Gucci’s creative director Michele, perhaps sensing the inevitable, claimed it was homage, and used the opportunity to welcome Dap into the fold. Late last year, the fashion house set him up with this handsome brownstone atelier and furnished him with bolts of Gucci fabric, prints, embroidered patches, and hardware. Now Dap is firmly within the orbit of François-Henri Pinault’s Kering group. Clients are booked both through Dap himself and through the fashion house. And this summer, the first Gucci-Dapper Dan collection was released.

Does he miss operating outside the box? “Let me give you a parable today, right?” Dap says rather cryptically. “During my days on the street, I didn’t like selling drugs, but I liked breaking drug dealers, so I became a professional gambler. Do I miss breaking drug dealers? Yes. But do I miss gambling? No.”

Though Dap is closely associated with hip-hop, to really understand his life’s work, you have to peel back the years to when he was a boy growing up in a working-class family and living at Lexington and 129th in the ’50s. “I have two older brothers who were big jazz fans,” he explains. “I remember going to watch Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers. I was in awe of those guys. They were my icons.”

Dap wasn’t simply inspired by the debonair style of the jazz cats. Rather, it was the very project of jazz itself that inspired him, 30 years later, to start remixing luxury fashion labels for his own purposes. Though on the surface, an outré Dapper Dan Louis Vuitton jacket and a scorching sax solo by Eric Dolphy might seem disparate, they beat with the same heart. Both take products of the dominant white culture—a brass instrument in one case, stodgy European luxury in the other—and twist them into an authentic expression of black culture.

According to James Newton, a professor and jazz historian at UCLA, the birth of jazz occurred thanks, in part, to the defeat of the South in the Civil War. After the Confederate States Army was disbanded, military musicians left behind their bugles, cornets, clarinets, oboes, and trumpets. Using the discarded marching band instruments, these proto-jazz musicians used the polyrhythms of African music and summoned from their horns blue tones that expressed their sorrow. “There was a real dialogue happening,” says Newton.

Dap sees his appropriation, over 100 years later, as part of the same historical movement. “There was never a period when African-Americans and people of colour did not extract from the culture that was responsible for us being here,” he says. And just as jazz was dismissed as a perversion of European culture, as “the Devil’s music”, his creations were labelled knockoffs and counterfeits. And just as that designation didn’t matter to early jazz musicians, it didn’t matter to him and his clients. “I started with the hustlers and all those who thumbed their noses at society, saying, ‘I don’t care if it ain’t real,’ ” he says. “They didn’t buy into, ‘Is this thing real?’ They knew they looked fly.”

Like any trailblazer, especially an African-American one, Dap has had to work twice as hard to change the game, once to overcome racism and again to alter the status quo. The day before I meet him, he has seen the great African-American ballerina Misty Copeland perform in Don Quixote with the American Ballet Theatre, and the performance resonated on two levels. First, tilting at windmills. “The only difference between me and Don Quixote,” says Dap, “is that he was fighting windmills and lost. I was fighting windmills and won.”

Which brings us to the secondary lesson: how to get ahead on a stage angled against you. “The parallel you can draw with Misty, with myself, with Obama, with Tiger Woods, and with Jackie Robinson is that you can spit on us or spit at us and we won’t stop. Our presence is going to be felt in a powerful way,” he says. “Misty had to be goddamn good, Obama had to be goddamn good, Jackie Robinson had to be goddamn good. I had to be goddamn good.”

These days, more people know John Coltrane’s cover of “My Favorite Things” than the 1959 original. Beyoncé and Jay-Z run the Louvre, and Gucci pays homage to Dapper Dan, not the other way around. Reclining on a sofa and looking fly AF in his Gucci attire, in his own atelier, Dap takes a moment to reflect. “If the mountain won’t come to Muhammad, then Muhammad must go to the mountain.” He smiles. “And,” he says, gesturing at his current station in life, “they came. They came.”

Photos of the Gucci-Dapper Dan collection courtesy of Gucci.

_________